Sponsored Content

During the Civil Rights Movement, Louisiana achieved many firsts, thanks to the innovation and dedication of its citizens.

In 1953, it held the movement’s first bus boycott, brilliantly creating a system that provided free rides for those boycotting public buses. The free ride system used in Baton Rouge was duplicated in Montgomery two years later during the bus boycott there.

Louisiana was also the first state to integrate an entire school system, beginning in November 1960 when four six-year-old girls walked into two all-white elementary schools in New Orleans.

To protect civil rights workers and protestors in the small mill town of Jonesboro, the Deacons for Defense and Justice was formed. The Deacons were mostly composed of family men who were also veterans. There was a strict code that Deacons had to follow. It was successful and slowly gained the respect of lawmen in the area. Chapters of the Deacons for Defense and Justice spread across the state and into Mississippi and Alabama.

While other marches may have more notoriety, the Bogalusa to Baton Rouge March in August 1967 was longer, covering 105 miles as it brought needed change to hiring practices and voting.

Touring the state, from New Orleans and Natchitoches to Baton Rouge and Bogalusa, will give travelers an admiration for all that Louisiana and its people have achieved as they fought to end segregation and to achieve equal rights for all.

New Orleans

Dooky Chase’s Restaurant

In a city where food is always front and center, it makes sense that a civil rights tour should begin at a restaurant bold enough to break the law so that everyone could break bread — and eat stuffed shrimp — together.

In 1946, when newlyweds Dooky Chase Jr. and Leah Chase took over the sandwich shop Dooky’s dad had opened, they made it clear that everyone was welcome at Dooky Chase’s Restaurant. The Chases defied the status quo. And their restaurant quickly became a gathering place for people doing important work, especially those who were leading the Civil Rights Movement. National and local civil rights leaders would meet in the upstairs dining room planning lunch counter sit-ins, boycotts, marches and protests. Leah Chase famously said, “I like to think we changed the course of America in this restaurant over a bowl of gumbo.” The couple often provided food at Civil Rights meetings and to demonstrators who had been arrested and jailed.

Dooky and Leah are now gone, but Dooky Chase’s welcoming ways continue, with grandson Edgar “Dook” Chase IV at the helm. Groups can dine on fare enjoyed by everyone from Beyonce and Barack Obama to James Baldwin and Ray Charles. Leah Chase’s collection of works by African American artists makes already elegant dining spaces a visual feast. Two private dining rooms are available, and given the restaurant’s fame and its food, reservations are recommended.

Dooky Chase’s is one of many Black-owned restaurants to try in New Orleans. New Orleans & Company lists more than 80 possibilities.

New Zion Baptist Church

Black churches were central to the Civil Rights Movement in Louisiana, and in New Orleans, this still-active church on Third Street was a major gathering place. In February 1957, in fact, a group of ministers from across the south founded the Southern Leadership Conference (now the Southern Christian Leadership Conference).

Louisiana Civil Rights Museum

The Louisiana Civil Rights Museum opened its inaugural exhibit at the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center in October 2023. The museum’s exhibits celebrate the heroes who protested, staged boycotts and sit-ins, signed up voters, held fundraisers and challenged segregated schools. Videos from key events and oral histories of those who were there bring stories to life.

Tate, Etienne & Prevost (TEP) Center

Step inside McDonogh 19 Elementary, and experience what it felt like to be one of the three six-year-old Black girls who integrated this all-white school. That’s one of the stories told at the Tate, Etienne and Provost Center, a museum that focuses on civil rights and New Orleans’ Black history. It owes its existence to Leona Tate, one of the three young girls who walked into McDonogh 19 in 1960. The museum opened in 2022 and visitors have since applauded the genuineness of the stories it tells and the staff who tell them (which often include Tate).

Baton Rouge

If a tree could talk, the Bicentennial Oak at the Old State Capitol could tell quite a story about how it shaded Black bus riders, waiting for free rides organized by local churches during Baton Rouge’s bus boycott in 1953. The boycott worked — within three days, buses were mainly empty; within eight, city leaders agreed that Black passengers would no longer have to stand when seats were open in the segregated white section. Two years later, the Montgomery Bus Boycott modeled a free ride system after Baton Rouge’s. The old oak still stands, and the Old Capitol, now a museum, welcomes tour groups.

Louisiana’s current state capitol is also a civil rights site. The longest march of the movement ended there, a march that resulted in improvement in employment practices for Blacks in Louisiana workplaces. The capitol, a striking 450-foot tower that is the tallest state capitol in the country, offers a wide view of the city and Mississippi River from its observation deck.

Students from Southern University were also active in civil rights protests. In 1960, many of those who held sit-ins at downtown lunch counters were arrested, jailed and later expelled from school. The school offers tours of its campus on weekdays.

Fuel Stops: If the air smells of fried chicken, the Chicken Shack must be nearby. It’s the capital’s oldest continuously running business. At Zeeland Street, chef Stephanie Phares constructs creative concoctions like Acadian Po’Boys. Jamaica meets Louisiana with dishes like Caribbean Pastalaya at Bullfish Bistro. For a list of 50 group-friendly restaurants, visit the Baton Rouge CVB’s website.

Pineville

In the state’s middle, Pineville is home the Louisiana Military Maneuvers Museum at Camp Beauregard. The museum tells the story of the Louisiana Maneuvers, held in 1940 and 1941, which were a series of large-scale U.S. Army training exercises in central and western Louisiana, involving over 400,000 troops. These maneuvers were crucial for preparing the Army for World War II, testing new equipment, strategies, and officer capabilities. The maneuvers were conducted under simulated wartime conditions, with mock battles, river crossings, and even the use of wooden rifles and flour sack bombs. Many notable military figures, including George Patton, Dwight Eisenhower, George Marshall and Omar Bradley, were involved in the maneuvers.

The lessons learned during the maneuvers contributed significantly to the success of the Allied forces in World War II, and according to the National WWII Museum, the exercises also helped develop the Army’s ability to conduct large-scale mechanized operations.

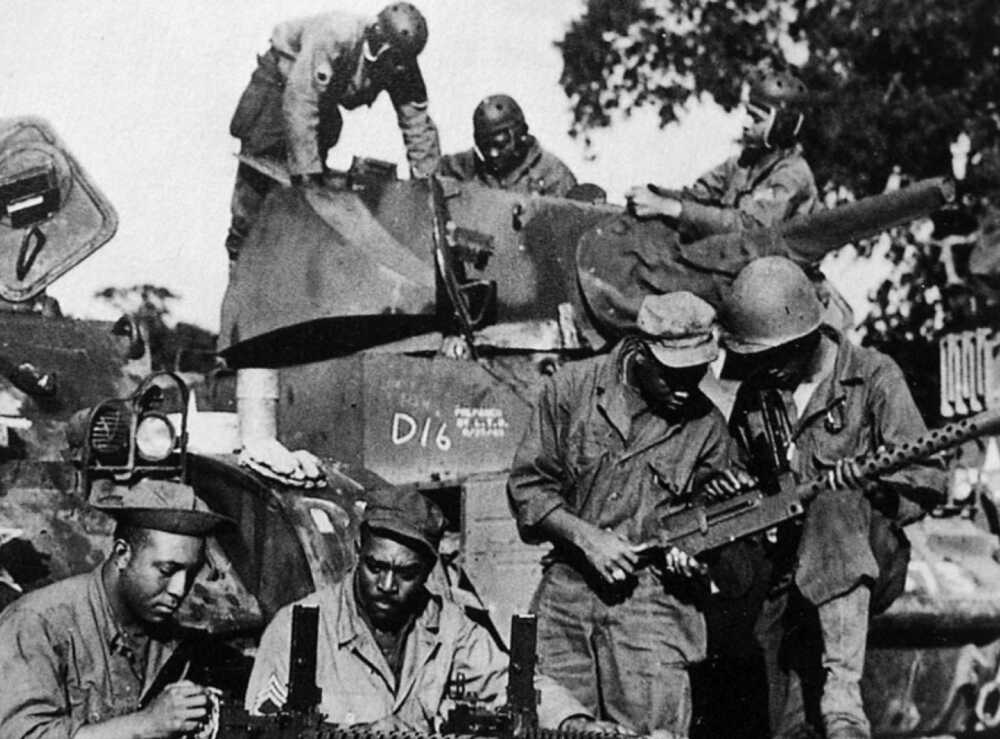

At the museum, visitors can learn about a fierce World War II battalion of Black soldiers nicknamed the Black Panthers and later Patton’s Panthers that trained at Camp Beauregard. Officially known as the 761st Tank Battalion, the experimental unit was similar to the Tuskegee Airmen.

Exhibits describe this fighting force’s impact. It supported eight infantry units in Europe, including Patton’s; liberated more than 30 towns; and was honored with multiple medals. It also had a lasting impact in terms of equality. The success of the 761st and the Tuskegee Airmen convinced President Harry S. Truman to desegregate the U.S. Armed Forces in 1948. Books have been written and documentaries/movies have been produced on the 761st Tank Battalion.

Fuel Stops: Alexandria is rich in good restaurants. At Quebedeaux’s Cajun Café, everything from tasso to sausage is made in house. USA Today chose it as one of the top places to eat in the U.S. Pamela’s Bayou in a Bowl is like eating at Grandma’s with meatloaf, smothered pork chops and yams. The Bentley Room at the four-star Hotel Bentley is known for its upscale take on the humble catfish. In Pineville, it’s Pop’s Place for plate lunches or Southern Creations for buffet lunch. For a restaurant with a 50-year track record for delicious catfish dinners, try Cajun Catfish House.

Lafayette

There’s more to this spirited Louisiana city than swamp tours. Much of Lafayette’s spark comes from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, the second-largest public college in the state.

In 1954, the college then known as Southwest Louisiana Institute became the first school in the Deep South to desegregate after four Black students successfully sued in federal court to be admitted. The Pillars of Progress Memorial pays tribute to those first Black students.

Fuel Stop: Head for the Downtown Food District, where 37 dining options line Jefferson and nearby streets. Many offer the Creole and Cajun foods the region is known for. And perhaps hone in on the city’s leading Black-owned eateries. At Noah’s Cafe, a former university football star broils delicious burgers at a restaurant known for good food, games and live music.

Creole Lunch House is a favorite for plate lunches. Meet hungry college students at KOK Wings and Things, right across from campus. For a sugary conclusion, order pralines at Sweet Envie.

Natchitoches

At Cane River National Heritage Area, a new visitors center in a restored train depot is one of the few places to get a clear picture of segregation.

The Texas and Pacific Railroad Depot’s two waiting areas, one for whites and one for Blacks, have been accurately restored. The difference in the two is striking. The white waiting area is elegant and spacious; the waiting area for Black passengers is basic and barebones.

Exhibits also describe the many people who passed through the station: Black soldiers who departed from there to fight in World War II and returned with a new world view, ready to fight for equal rights at home, and the hundreds of Black families who boarded trains for better jobs and lives in the North during the Great Migration.

At nearby Cane River Creole National Historical Park, Oakland and Magnolia plantations are the focus, and at these restored plantations, visitors learn about the lives of the enslaved people who worked there. More than 60 historic buildings survive at Oakland, and a number are open to the public. At Magnolia Plantation, a blacksmith shop, tenant cabin and cotton gin barn are open Wednesday through Sunday for self-guided tours.

Fuel Stop: A stop in Natchitoches (Nak-a-tish), the oldest settlement in the Louisiana Purchase, is a must. Founded in 1714, the pretty town retains its European air. Local guides give free walking tours of the 33-block National Historic Landmark District. For food and drink after a stroll, groups can choose from a dozen locally owned downtown restaurants serving Creole, Cajun and Southern foods.

Bogalusa

In most towns, churches fueled the Civil Rights Movement, but that was not the case in Bogalusa, 70 miles north of New Orleans, across the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway. Unfair employment practices at a local paper mill led activists A.Z. Young, Robert “Bob” Hicks and others to organize a march from Bogalusa to the state capitol in 1967. The 105-mile march is said to be the longest of the Civil Rights Movement. At the start, some 20 walkers left Bogalusa. Ten days later, 600 marchers, along with 2,200 state police and national guardsmen, arrived at the state capitol. Young presented a list of grievances to Governor John McKeithen. This effort helped lessen discriminatory hiring and election practices.

Fuel Stops: Throughout Louisiana, fish and seafood rule. Warner’s Fish House is a local favorite. For smoked meats, there’s nothing better than Nothin’ But Tha Smoke.

For more information, visit the Louisiana section of the U.S. Civil Rights Trail website.