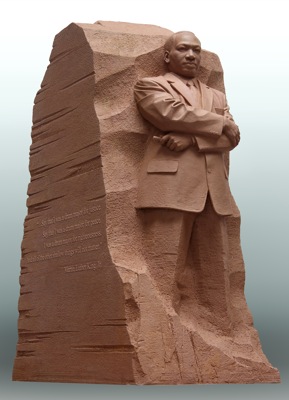

Courtesy Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial

Courtesy Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial

On Aug. 28, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington and delivered one of the most famous speeches in American history.

The “I Have a Dream” speech before nearly a quarter-million people who had gathered on the National Mall to push for civil rights for African-Americans included the sentence: “With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.”

This Aug. 28, on the 48th anniversary of the speech, the Martin Luther King Jr. National Memorial will be dedicated on the Mall’s Tidal Basin between the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials. Its main features reflect King’s words.

“The first thing you will encounter are two large pieces of granite that look like a mountain. It is called the Mountain of Despair,” said Harry E. Johnson Sr., president and CEO of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Project Foundation. “They are 30 feet tall with a 12-foot-wide opening between them.”

On the other side of the mountain, in a crescent-shaped mall, quotations from 14 of King’s speeches are inscribed on a 500-foot-long granite wall.

“You have not [yet] seen Dr. King until you walk toward the Tidal Basin,” said Johnson. “Sitting near the water is a large stone that looks like it is carved out of the Mountain of Despair. Dr. King is carved out of the Stone of Hope, looking across at Thomas Jefferson.”

The statue of King with his arms folded seems to emerge from the 28-foot-tall stone.

The four-acre site is set amid Washington’s famous cherry trees, which bloom each year around April 4, the date of King’s assassination. An additional 185 cherry trees have been added to the memorial’s landscape.

“When you come during the Cherry Blossom Festival, it is one of the best places to be,” said Johnson. “It is a very serene setting and a reflection of what Dr. King meant to America and indeed the world.

“We hope people will leave with Dr. King’s message of hope, democracy, justice and love.”

Nearly a half-century after his death, King still resonates with African-Americans. In a poll of 1,018 African-American travelers conducted in December by the Washington-based tourism marketing research firm Mandala Research, one-third said they were very likely to take a trip where stories and sites related to King and the civil rights movement are available.

More than half of the travelers surveyed said they would be more inclined to visit attractions that offer exhibits about African-American history and culture.

Groups can trace the history and legacy of King at several sites in the South, from his birth in Atlanta through his early ministries to his national role in the civil rights movement and his assassination in Memphis, Tenn.

Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site

Atlanta

King was born Jan. 15, 1929, in a two-story Queen Anne-style house on Auburn Avenue in Atlanta’s then predominantly black Sweet Auburn neighborhood. The house was about a block from the Ebenezer Baptist Church, where his father was pastor.

Now managed by the National Park Service, the house, where King spent the first 12 years of his life, has been restored to its 1930s appearance.

About one-third of the items in the house, including the piano on which King and his siblings took lessons, are original. However, the house is open only for ranger-guided tours that are limited to 15 people at a time. Tickets can be reserved only on the day of the tour, and exceptions are not made for groups, which are limited to a total of 45 tickets.

However, groups can visit the historic sanctuary of the Ebenezer Baptist Church, which is also part of the national historic site. King was co-pastor there with his father from 1960 until his death in 1968.

The site includes the King Center, where some of his personal possessions are displayed, and a visitors center with films and exhibits. The graves of King and his wife, Coretta Scott King, are located amid a reflecting pool at the King Center.

Montgomery, Ala.

King first rose to national attention during the bus boycott of the mid-1950s in Montgomery, where he became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in 1954 at the age of 25.

Groups can tour the church, now known as the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, where a 10-foot-by-47-foot mural that depicts scenes from King’s life, beginning with the bus boycott, covers a wall in the basement.

“The basement is the same as when Dr. King was here,” said a guide.

The nine-room house where King and his family lived from 1954 to 1960 is a museum and has been restored to its appearance when the Kings lived there. Much of the furniture in the living room, dining room, bedroom and study is original.

An interpretive center adjacent to the house has photos and exhibits about the history of the church and King’s time in Montgomery, including the bombing of the parsonage during the bus boycott. A reflection garden is located in the back.

At the stirring Civil Rights Memorial at the Southern Poverty Law Center, water flows over a large, circular black-granite table containing the names of 40 people killed in the civil rights struggle between 1954 and 1968.

Water also flows down a curved black-granite wall behind the table where the following words from the Bible that King often quoted are inscribed: “We will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

The memorial was designed by Maya Lin, who also designed the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington.

www.visitmontgomery.com

www.dexterkingmemorial.org

Birmingham, Ala.

In the spring of 1963, as part of a coordinated effort to end segregation in Birmingham, King and other civil rights leaders forced confrontations that led to their arrests. In response to a group of local clergy who criticized their actions as being too activist, King wrote a lengthy letter to them from his cell defending the movement’s actions.

“Letter From Birmingham Jail,” written on the margins of newspapers and the backs of legal papers and smuggled out in sections by King’s attorney and aides, articulated the basic tenants of the nonviolent civil rights movement, was widely reprinted and became a manifesto of the movement.

Part of the cell where King wrote his historic document is on display at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

“We have the jail cell bar door where he wrote the letter,” said Lesley Bruinton, head of communications for the institute. “The exhibition looks like a jail cell. If you are inside and turn around, there are excerpts from the letter, and above it, coming out of speakers, is King reading the letter.”

Bruinton said the original keys to the cell are also on display. “They are huge,” she said.

The institute takes a forthright look at the impact of segregation on all segments of everyday life and traces the struggle in Birmingham and the rest of the South for equal rights.

Although the exhibits deal primarily with Birmingham, there is a section about the March on Washington, and visitors can hear a recording of the “I Have a Dream” speech in an area that includes 1960s-era televisions in a false storefront showing news clips of police attacks on the Birmingham demonstrators.

The institute is also a center for education, research and discussion of human rights issues and chronicles the continuing struggles for human rights around the world.

“We want to keep the issues on the table,” said executive director Lawrence Pijeaux Jr. “We want to provide a venue for the open discussions of ideas.”

A statue of King is one of several in the adjoining Kelly Ingram Park, where police, using water hoses and dogs, attacked protesters. Also across the street from the institute is the 16th Street Baptist Church, where a bomb blast on a Sunday morning in September 1963 killed four young black girls as they were putting on their choir robes.

Both sites became iconic images of the civil rights movement.

Selma, Ala.

Two years after the events in Birmingham, King was at the forefront of another clash with police, this time demonstrating in Selma for voting rights for African-Americans.

March 7, 1965, became known as Bloody Sunday; on that day, about 600 black protestors, ignoring a ban on protest marches by Alabama Gov. George Wallace, began a march from Selma calling for voting rights.

As the marchers crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, mounted police attacked, swinging billy clubs and firing tear gas. Televised images of the assaults created national outrage and were credited with helping secure the passage of the Voting Rights Act less than five months later.

After a federal judge overturned Wallace’s order, King led a five-day march of several thousand from Selma to the steps of the Capitol in Montgomery.

The Selma Tourism and Convention Bureau has developed a Martin Luther King Jr. Street Walking Tour that highlights several key sites in the protest, such as the Romanesque Revival-style Brown Chapel AME Church, the starting point for the marches; the National Voting Rights Museum and Institute, which has plaster casts of the footprints of people who took part in the marches; and the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

The 54-mile route from Selma to Montgomery is a national historic trail administered by the National Park Service. The Lowndes County Interpretive Center is about halfway between Selma and Montgomery.

www.selmaalabama.com

www.nps.gov/semo/

Memphis, Tenn.

In the spring of 1968, King went to Memphis to support striking sanitation workers. On April 4, as he was leaving his second-floor room at the Lorraine Motel, he was shot and killed by a sniper.

The National Civil Rights Museum, which celebrates its 20th anniversary this year, occupies the former motel and a former rooming house across the street, from which the fatal shot was allegedly made.

The museum has interactive exhibits that trace the history of civil rights from the 1600s to the present. Several exhibits dealing with major events in the civil rights movement cover King’s participation in them.

“The Montgomery bus boycott introduces Dr. King to many of us in the movement. That is when he first became part of the movement,” said Barbara Andrews, director of education for the museum.

“The Birmingham Project C exhibit talks about the youth protests and Dr. King being jailed there. We have a re-created jail cell and his ‘Letter From Birmingham Jail.’”

Andrews said other exhibits that deal with King include the March on Washington, with audio excerpts from his “I Have a Dream” speech; the March Against Fear, in support of James Meredith integrating the University of Mississippi; and his work against poverty in Chicago.

A tour through the museum gradually progresses to the second floor, where it ends at Room 306, the room in which King stayed the night before he was shot.

The room has been re-created to appear as it did at the time of the assassination, with food-service trays with leftovers, half-empty coffee cups, King’s shaving kit in the bathroom and a newspaper on the bed.

The outside has also been maintained, and you can see the balcony where King was standing when he was shot.

“It’s a very emotional place,” said Andrews. “You feel a connection to Dr. King at that point. People are moved on many levels.”

“If you don’t feel something when you go through there, you are just not alive,” said Regena Bearden, vice president of marketing for the Memphis Convention and Visitors Bureau. “No matter how many times I have been through there, ending up in that room is an incredible feeling.”

An exhibit in the former rooming house deals with the assassination in detail, including the hunt for assassin James Earl Ray and the continuing controversy and conspiracy theories. After being caught, Ray initially confessed, but later retracted his confession and spent the rest of his life until he died in prison in 1998 unsuccessfully fighting for a trial.