Sponsored Content

Travel the U.S. Civil Rights Trail through Virginia, and you will hear stories of determined Black Virginians who faced constant challenges as they worked toward ensuring equal rights and freedom for all. Virginia’s four U.S. Civil Rights Trail sites — the Fredericksburg Civil Rights Trail, the Virginia Civil Rights Memorial, the Robert Russa Moton Museum and the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History in Danville — tell compelling, often untold stories. Follow the trail, listen and learn, and feel your mind and heart open.

Fredericksburg

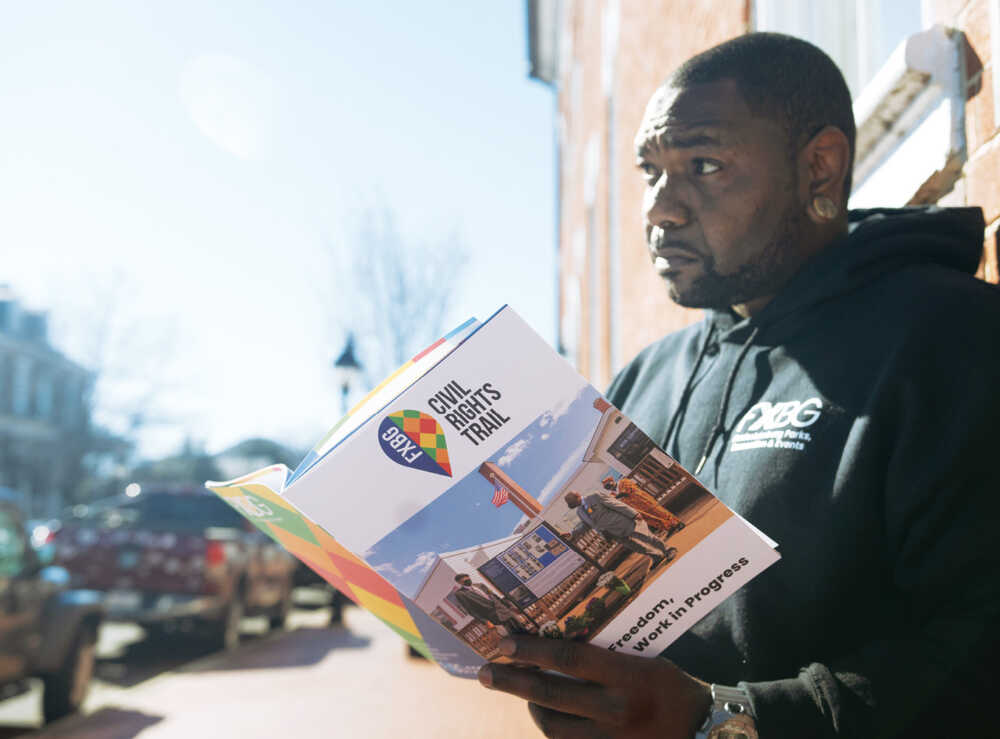

For tours coming from the Northeast, Fredericksburg can be the starting point for a civil rights tour. About 90 minutes south of Washington, D.C., the city is just off I-95. In 2023, it unveiled the Fredericksburg Civil Rights Trail, an impressive guide to sites tied to the civil rights movement and to African American history. The City of Fredericksburg, the James Farmer Multicultural Center at the University of Mary Washington and other UM students and faculty worked together for many years to do research and collect oral histories for the trail.

The result is a tour in two parts. The first is a 2.6-mile walking tour through the historic downtown district; the second is a half-mile walking tour of the UMW campus and a two-mile driving tour. Maps and updates are available at the Fredericksburg Visitors Center, which is also the starting point of the downtown tour.

Among the stops are the former Trailways/Greyhound bus station, which was the first stop for the Freedom Riders in 1961; the old City Hall, where many legal challenges were made to the accepted practice of segregation; and Liberty Town, a neighborhood built for Black residents in the late 1800s by a Black entrepreneur.

The tour goes beyond the physical sites thanks to recorded interviews with many residents who were involved in the movement and who share their memories. The stories run deeper than any history book, telling compelling stories that have gone untold, like the hatred and isolation one man faced as a Black student integrating a white school.

The partners chose the theme “Freedom: A Work in Progress,” and they aim for the trail to live up to that theme, as more sites and stories are added.

Fuel Stops: Fredericksburg’s black restaurant owners do more than cook. They find ways to support their community. For example, at Orleans Bistro, owner Tisha Johnson supports local nonprofits that aid the elderly and children, as she delivers Southern and New Orleans specialties — from fried chicken gizzards and alligator bites to seafood gumbo and shrimp and grits. HOPE Heroes is also on a mission to serve. Book one of its three private dining spaces (there’s no charge) and learn how the couple behind this concept is helping feed people at a restaurant where HOPE means “Helping Other People Eat.” Enjoy Jamaican-style curry chicken, jerk chicken, oxtail and other dishes at Taste of Trelawny. The veteran-owned business realizes not everyone has tasted Jamaican cuisine and so it offers small samples of most dishes. At A. Smith Bowman Distillery, enjoy a complimentary tour and tasting of bourbon that put Virginia on the bourbon lovers’ map.

Leg Stretchers: Dash into the Made in Virginia store and stock up on Virginia peanuts or saltwater taffy. Or send “You’re Kind of a Big Dill” or Sweet and Salty Sampler gift baskets to someone back home. There are dozens of treats and gifts to choose from.

Make time to visit the Fredericksburg Area Museum. Its collection includes a wrenching permanent exhibition, “A Monumental Weight: The Auction Block” in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Richmond

The Virginia Civil Rights Memorial is an inspiring start to a civil rights tour of Richmond. In a plaza on the state Capitol grounds, the memorial honors 18 Virginians who worked to achieve equality for all. Each of the bronze statues is in action, moving forward, especially that of Barbara Rose Johns, the 16-year-old who organized more than 450 students to protest their inadequate school building in Farmville. The efforts of Johns and others depicted in the memorial would lead to the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling that declared segregation unconstitutional.

From the Capitol, it’s a few blocks to Richmond’s historic Black business district, Jackson Ward. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, this thriving Black neighborhood was called the “Harlem of the South,” and “Black Wall Street.” It was packed with Black businesses and professionals, including Maggie L. Walker, whose statue stands at the gateway to Jackson Ward and whose home is now the Maggie Walker National Historic Site, operated by the National Park Service and open for tours.

Walker was a formidable force, best known for being the first African-American woman in this country to found a bank. It would become Consolidated Bank & Trust, the oldest surviving Black operated bank in the U.S. She also founded a newspaper, was involved in education, and, in the days of Jim Crow, worked for civil rights.

The house where she lived from 1902 until her death in 1934 is furnished with many family pieces. The presence of those heirlooms adds a personal touch and helps visitors better grasp Walker’s remarkable story.

One-hour group tours are offered by the NPS Tuesday through Thursday, with reservations required two weeks in advance. Tours for the public are offered five times a day on Friday and Saturday.

Leg Stretchers: Take a self-guided tour of Jackson Ward by downloading the National Park Service historic Jackson Ward podcast tour or by contacting the NPS and requesting a tour map and transcript be sent by email.

If a self-guided tour doesn’t suit, consider a guided one with a fourth-generation Jackson Ward resident. Gary L. Flowers covers important ground on his 1.5-mile, 20-stop walking tours of the neighborhood where he grew up. His Walking the Ward tours delve into the neighborhood’s social and cultural aspects and its economic and educational opportunities as he describes the work of leaders like Maggie Walker and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. (Minimum of 10 people, $20 per person).

The Black History Center and Cultural Center of Virginia resembles a fortress — it was built as an armory, after all — but inside, it is sleek and contemporary, filled with stories that inspire. The museum aims to tell stories beyond those of Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King and other well-known Black civil rights leaders. One of its permanent exhibits, of the Richmond 34, recounts how students from Virginia Union University, inspired by a speech given by King and students in Greensboro, North Carolina, staged a sit-in at downtown Richmond’s segregated department stores. Another is devoted Oliver White Hill, Sr., a civil rights attorney from Richmond, whose legal prowess helped end “separate but equal.” He also won lawsuits involving equal pay for black teachers, voting rights and employment protection. The museum’s special exhibitions take interesting approaches: a look at contributions made by Black doctors, dentists and other health professionals; the legacy of Black Catholics in the state; the stories of the enslaved people at Jefferson’s Monticello.

Open Wednesday through Saturday, from 10 am to 5 pm, the museum is one of four places in the United States and 22 in the world chosen by UNESCO for its Network of Places of History and Memory. All the sites chosen tell stories of the slave trade and its victims. Admission is $10 for adults and $8 for seniors.

Just a couple of blocks from Maggie Walker’s statue, a joyful statue made of steel honors another native of Richmond and the Jackson Ward, William “Bojangles” Robinson. Robinson, a dancer and entertainer in the 1930s and 1940s, helped break the color barrier in Hollywood and starred in a dozen films. The statue captures Robinson’s jaunty style as he dances down the steps. Funding for the statue came from the Astoria Beneficial Club, created by 22 men who “believed that the barriers to full citizenship could be eliminated with patience, planning and timely action.” They led efforts to gain voting rights, equal opportunity in employment and end segregation. The statue honors Robinson’s giving spirit — he donated a significant sum to have a streetlight installed at an intersection in Jackson Ward where several Black schoolchildren had been struck by cars.

Walk or ride a bike along the Riverfront Canal Walk. The 1.25-mile loop takes visitors past public art, history exhibits and waterfront restaurants as it follows the James River and Kanawha Canal. Bike and Brunch Tours offer Black history biking or walking tours.

Fuel Stops: Appetizing smells waft from plentiful restaurants in and around Jackson Ward. Groups can head in different directions as they seek everything from farm to table, Mexican, Indian, Thai, barbecue or burgers and fries. The soul food at Mama J’s is highly recommended. Richmond is rich in black-owned restaurants, including Nomad Deli, 521 Biscuit & Waffles, Sweet Spot, Ruby Scoops and Urban Hang Suite. For more black-owned restaurants in Richmond, check out this list.

Farmville

From Richmond, head southwest for about an hour through the Virginia countryside to Farmville (pop. 7,500) to visit the Robert Russa Moton Museum.

The red-brick, one-story school built in Farmville for African American students seems unassuming, but Robert Russa Moton High School’s size did not equal its impact on American society. The school was the site, in 1951, of a student-led effort to end the inequality that its students faced. Twice as many students as the school was designed to hold were crammed into its eight classrooms and auditorium. The county’s solution? Throw up some flimsy, poorly heated shacks as temporary classrooms.

Today, the school building, a National Historic Landmark, serves a higher purpose — to educate people about the nonviolent student protest that led to a lawsuit that would become part of the landmark lawsuit Brown v. Board of Education.

The museum’s six galleries take visitors through 12 years of legal battles and community pushback triggered by the strike of 450 students, who were led by 16-year-old student Barbara Johns. It explores how the state closed public schools for five years after the Supreme Court ruled segregation was unconstitutional. It concludes with the opening, in 1963, of the Kennedy Administration’s Prince Edward Free Schools.

As Don Baker wrote in the Washington Post magazine, “[The 1951 Moton Student Strike] marked the start of the modern civil rights movement… [and] forever changed the landscape of American education.”

Museum hours are noon to 4 pm. Monday–Saturday and by appointment, and admission is free. Guided tours of five or more can be scheduled in advance.

Leg Stretchers: The Farmville Civil Rights Walking Tour takes in 17 sites that were significant during the civil rights movement. Each site is marked by a tour logo stamped on the sidewalk. Free brochures with a map and descriptions of each stop are available at the museum.

The two-mile route begins and ends at the Moton Museum. Sites include churches where civil rights organizers met and organized, the site of a JJ Newberry’s where sit-ins were held and two monuments, one that remembers the Confederacy and the other honoring those who’d worked to expand personal freedoms and equality.

Add a little shopping to the tour by visiting one of Green Front Furniture Company’s 13 shops or warehouses — close to a million square feet filled with furniture from around the world. If there’s time, stroll Longwood University’s campus and take in its architecture and small college feel. For a scenic overview, make a stop at High Bridge, a wooden path that stretches 2,400 feet over treetops and the Appomattox River

Fuel Stops: For a small town, Farmville has a lot of local flavor. At Charley’s Waterfront Café, the importance of agriculture is clear. Charley’s, like several other businesses in town, is in a restored tobacco warehouse. Meals can start with roasted red pepper and crab soup, move on to St. Louis ribs and end with a blondie brownie sundae. If weather permits, diners can enjoy a deck overlooking the Appomattox River. Below Charley’s, the Virginia Tasting Cellar offers sips of Virginia wines, craft beers and ciders. The Fishin’ Pig is known for fried catfish, a roomy patio and live music on Wednesdays.

Side Trip: Schedule a farm tour at Bright Eyes Alpacas and learn more about these soft and sociable creatures.

Danville

Danville (pop. 42,000) is about two hours south of Farmville on the North Carolina state line. The city tells its complicated civil rights story through The Movement, a permanent exhibit at the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History. “The Movement” tells the story of residents who began a series of nonviolent actions in 1963 to protest segregation in the town, especially in government and employment. Fairly quickly, white authorities reacted with clubs and firehoses — violent strategies like those used in Selma and Birmingham, Alabama, and Little Rock, Arkansas. The violent reaction brought national civil rights leaders to Danville including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. But litigation and court effectively prevented the movement from making any progress even on voting rights and other major issues.

Three other permanent exhibits further aid in understanding African American life in an area that had once been closely aligned with the Confederacy. They include the Camilla Williams Exhibit, a tribute to the opera star from Danville who helped break color barriers; Behind the Lines, examining Danville’s role in the Civil War — it is known as “the Last Capital of the Confederacy,” and the Danville Hall of Fame, honoring influential residents, including Wendell Oliver Scott, the first African American to compete in and own a NASCAR team.

The museum is open Thursday through Sunday and offers guided tours at 11 and 1 pm. Admission is $12 for adults and $10 for seniors.

Leg Stretcher: Karine “Ressie” Luck-Brimmer, an independent historian and genealogist, has turned those passions into Our History Matters, a tour business in Danville. She tells the stories of important African Americans, whose contributions have often been overlooked. Her Red Trolley Civil Rights Tour, which can also be done on a motorcoach, explores the sit-ins and strikes organized by civil rights activists that led to the violent Bloody Monday in Danville.

Her Black in the Dayz Community Guided Walking Tours explore cultural history with walks through African American communities and can include storytelling by community elders on neighborhood porches and a soul food picnic.

Saturday mornings, May through October, take in the Danville Farmers Market where local producers sell fruits, vegetables, meats, honey, jellies, homemade baked goods, jewelry, art and other gifts.

Fuel Stops: The Golden Leaf Bistro, in the Tobacco Warehouse District, offers a large patio, three private dining rooms and live music on weekends, not to mention starters like Bang Bang Shrimp Egg Rolls and a lineup of steaks and seafood. You know you’ve come south at the Checkered Pig, where smoked meats are in the spotlight, and starters include pork rinds and fried dill pickles. The Schoolfield Restaurant is also known for steaks and seafood, but the fried green tomato chicken and the Old Bay fries are also tempting. Sit a spell, sip a Fast Mail Mild Ale in Ballad Brewing’s chic taproom, a restored 1891 warehouse, and tackle trivia or bingo.